|

In the spring

of 1945, the hastening end of World War II brought chaos

and disruption to the San Diego area. Returning

servicemen vied for non-existent jobs at dozens of

peace-ravaged companies which had made their livings

from defense contracts. At the giant Consolidated Vultee

aircraft plant, lay-offs and short hours replaced

overtime seven day weeks. John Liefeld, a 32-year-old

former Chrysler engineer who'd spent the war years at

Convair, knew it was only a matter of days before he too

would be let go. Anxious to get back into the automobile

business, he began looking for a new job.

Liefeld's brother

introduced him to a strange character he'd met in a bar,

named S.A. Williams. Williams was basically a promoter,

who had dabbled in dozens of money-making schemes. In

1945, he was making a handsome living by buying up

poorly-managed restaurants, upgrading them and reselling

at a profit. Williams thought he saw a rare opportunity

for his talents in the hungry postwar car market, and

had some vague notion of building his own small car.

He agreed to bankroll

Liefeld in the production of a prototype minicar. They

set up a small shop on India Street in San Diego, where

Liefeld and a few friends from Convair began to

construct a simple rear-engine Dodg'em car, powered by a

16 hp two-cylinder Briggs and Stratton engine. This was

connected to the rear wheels through a rudimentary

centrifugal clutch and chain arrangement. With a bulbous

fiberglass body, the whole car weighed less than 600

lbs. Liefeld christened it the "Iron Monster," though

officially, it was called the "Bobbi-Kar" after

Williams' son.

It was painfully

inadequate. Liefeld's group immediately began work on a

successor, this time using a Hercules ZXB, the venerable

25 hp Four that found its way into many a postwar

minicar prototype. Its dull powerplant and lumpy body

notwithstanding, the Bobbi-Kar did incorporate some

interesting technical features. It used an "X" frame

tubular chassis, suspended by B.F. Goodrich's "torsilastic"

suspension. (Very simply, the suspension consisted of a

central steel core encased in a rubber cylinder encased

in a steel shell. A trailing arm was attached to the

outside shell, the inner steel connected to the chassis

and the rubber acted as both spring and shock absorber.)

Automotive

Industries commented, "The power application

contains several innovations, The engine, flywheel,

clutch and housing, transmission and differential (all

of which were proprietary parts) have been combined into

a single compact unit... suspended on three point rubber

mountings between the side members of the frame.

Propeller shafts extend from the differential to the

driving spindles of the rear wheels. Each propeller

shaft has two universal joints. By removing four bolts

from the flange of each inner universal joint, and three

engine mount bolts, it is possible to remove the entire

power unit from the automobile in a matter of minutes."

Williams now showed

his fantastic sales ability. He contacted the four major

movie Newsreel studios--the mass market media in the

pre-TV days of 1945--and managed to get news clips about

the Bobbi-Kar into all four. Newspapers picked the story

up as well, and soon, according to Liefeld, people from

all over the world started sending in money to buy

Bobbi-Kars. On his lawyer's advice, Williams opened a

separate bank account for these funds, holding them

until such time as there were Bobbi-Kars to sell. But

the overwhelming public reaction spurred him to bigger

plans.

Solar Industries,

another of San Diego's bankrupt defense contract

companies, had a large plant for sale. Williams bought

it late in 1945 for $80,000, and installed Liefeld and

staff in a small corner. Huge new signs plastered the

outside, however, taking full advantage of Bobbi-Kar's

impressive new home. But it wasn't big enough for

Williams. Consolidated Vultee plant #2--the very

building Liefeld and his friends had worked in

throughout the war--was now lying empty. Williams leased

it through the War Assets Administration and moved his

still-tiny group into the administrative offices of the

huge aircraft complex. Liefeld remembers in amazement

that less than a year after he'd labored at Convair as

merely one of hundreds of young engineers, he was back

in the same building, installed in what had been the

office of Major Fleet, the owner of Consolidated Vultee.

Leftover machinery

lined the Convair plant, so Liefeld was instructed to

make it look as if Bobbi-Kar was preparing to use it in

the production of their new car. With this impressive

establishment behind him, Williams started selling

franchises for future "kars" to eager would-be dealers.

His lawyer advised him that since the Bobbi-Kar

agreement clearly specified that the franchise earned

dealers the right to handle kars only "if and when" such

kars were built, Williams had every right to be selling

them. Some 800 investors took the plunge.

The California

Commissioner of Corporations was not as sanguine as

Williams' lawyer. Soon the SEC was also on his trail,

greatly interested in his announced intention of selling

unregistered stock. In the ensuing investigation, it was

revealed that Williams had previously served prison time

on another swindle. His operations in California were

virtually shut down. Undaunted, Williams attempted to

form another corporation under the lenient Delaware

laws, but was unable to obtain a needed clearance from

the State of California. Had this gone through, he

intended to float a $5.5-million stock issue. As it was,

Bobbi-Kar was stuck between its creditors and the SEC.

Around the same time,

in February, 1946, George Keller showed up in Liefeld's

office. Keller was then in his mid-Fifties, a veteran of

28 years at Studebaker in South Bend. Vice-president of

Sales, he had clashed with manager Ken Eliot over the

question of distribution, and left the company. Ted

Zenzinger, Keller's assistant at Studebaker, says

"Keller was known as 'Big George.' He was extremely

honest, and known throughout the industry as a dynamic

salesman." Gene Hardig, the chief of Studebaker

engineering at the same time, remembers Keller as "very

well thought of at Studebaker, well liked and an

aggressive salesman."

Keller had stalked

out of Studebaker with not much more than an impressive

list of contacts in the automobile industry and the

shirt on his hack. When he came to visit Liefeld, he was

working as a salesman in his father-in-law's San Diego

Buick agency. Ever since the late Thirties, however,

Keller had been thinking about forming his own car

company, and had often discussed with Zenzinger what he

called "the ideal car for the poor man." His rationale

was simple. The big car makers controlled the major

market areas, but none was interested in trying to

produce a really inexpensive car that was no more than

basic transportation. Said Keller, "When you're bucking

Detroit, you're bucking a stone wall." He dreamed of

tunneling under it at the low-price end.

Liefeld hired Keller

as an advisor. Almost the same week, Williams let drop a

news story that was picked up by many papers. Bobbi-Kar,

he said, was looking for a new locale where they could

build cars without interference. The Birmingham, Alabama

Chamber of Commerce was trying to find industries to

replace the now-closed Huntsville Arsenal and

Bechtel-McCone Aircraft Corporation, which between them

had furloughed thousands of Northern Alabama workers. A

representative flew out to talk to Williams, and

Williams then flew back to Alabama. Within the week,

Liefeld received a telegram which said simply, "Put

everything on a flat car."

George Keller had now

begun to challenge Williams for control of the company.

Keller later wrote that "the investigation of the

Alabama facilities was made quickly-overnight as it

were-and an immediate decision was made to move

everything to Birmingham. Williams reported back to the

San Diego newspapers that he was making the move because

he had located better plant property, and besides, it

was easier to sell stock in Alabama than in California.

Nothing could be more absurd. Except that Williams,

without any automobile experience, could determine

whether or not the Bechtel-McCone buildings were

suitable for the production of Bobbi-Kars... but since

Williams was the sole owner, other employees were

powerless to do anything but move according to his

wishes, right or wrong."

Williams' prison

record followed him to Alabama, and he was told that be

could never be a director or officer of any Alabama

corporation. By now, in addition to Keller, Liefeld and

his handful of former Consolidated Vultee engineers who

had been with the company right along were ready for a

change. According to Keller, "There were a lot of other

members of this organization besides Williams who had

given freely of their time and effort for very little

financial gain, and who were more responsible for the

product than Williams-who was neither an engineer nor a

designer..,, nor does he have any background of

automotive experience."

Keller and his

Bobbi-Kar mutineers were ready to join up with anyone

who could pay the freight until Bobbi-Kar production

could begin. On September 13, 1946, Bobbi-Kar of Alabama

was established. The entire California company's assets

were transferred to the new corporation, in exchange for

capital stock. The two Bobbi-Kar companies between 1945

and 1947, collected some $292,677.50 for dealer

franchises, $126,599.50 as loans from prospective

distributors and customer deposits totaling $38,125.00.

According to a later stock prospectus, "all these funds

were expended in connection with the development and

promotion of an automobile and a dealer organization."

At this point,

however, Williams was still in control. But in March,

1947, a group of Alabama investors succeeded in making

Williams an offer he couldn't refuse. (He subsequently

returned to Southern California and was involved in two

similar small car schemes, the Towne Shopper and the

Elektrakar. Later still, he was reportedly convicted for

his part in a nationwide ring that distributed

counterfeit $20 bills.)

The confederates now

owned Bobbi-Kar of Alabama, one and the same company as

Bobbi-Kar of California. But this presented a problem,

for the new owners weren't sure they wanted to inherit

the 800 franchise dealers--many of them less than solid

representatives--that Williams had assembled.

Accordingly, on July 8, 1947, the Dixie Motor Car

Corporation was founded to take over the assets of

Bobbi-Kar for $30,000 in cash and a promise to pay back

the $38,500 received for customer deposits on

never-delivered Bobbi-Kars. Most of the corporate

officers of the two companies were the same, but the

dealers had been neatly cut off.

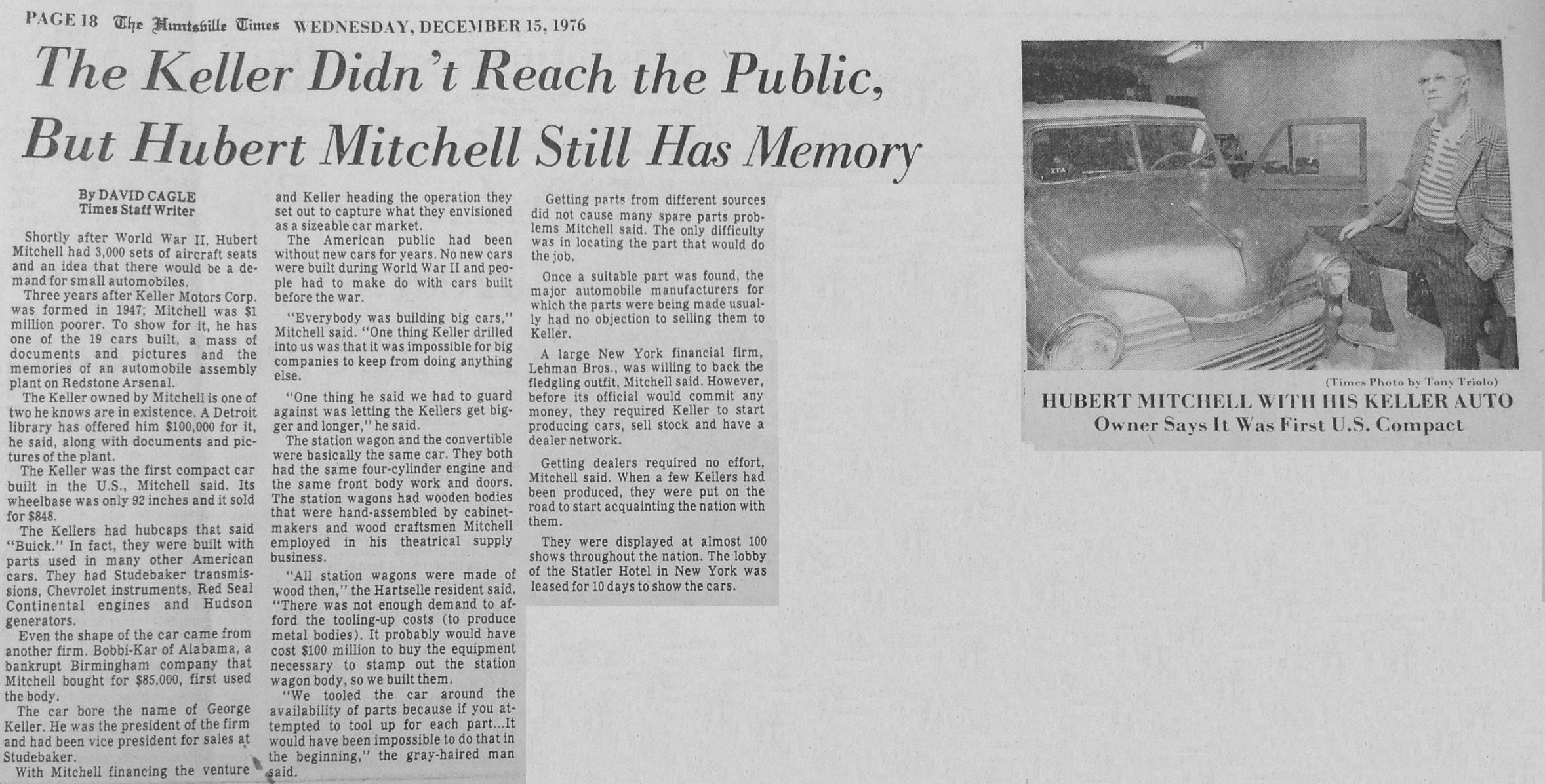

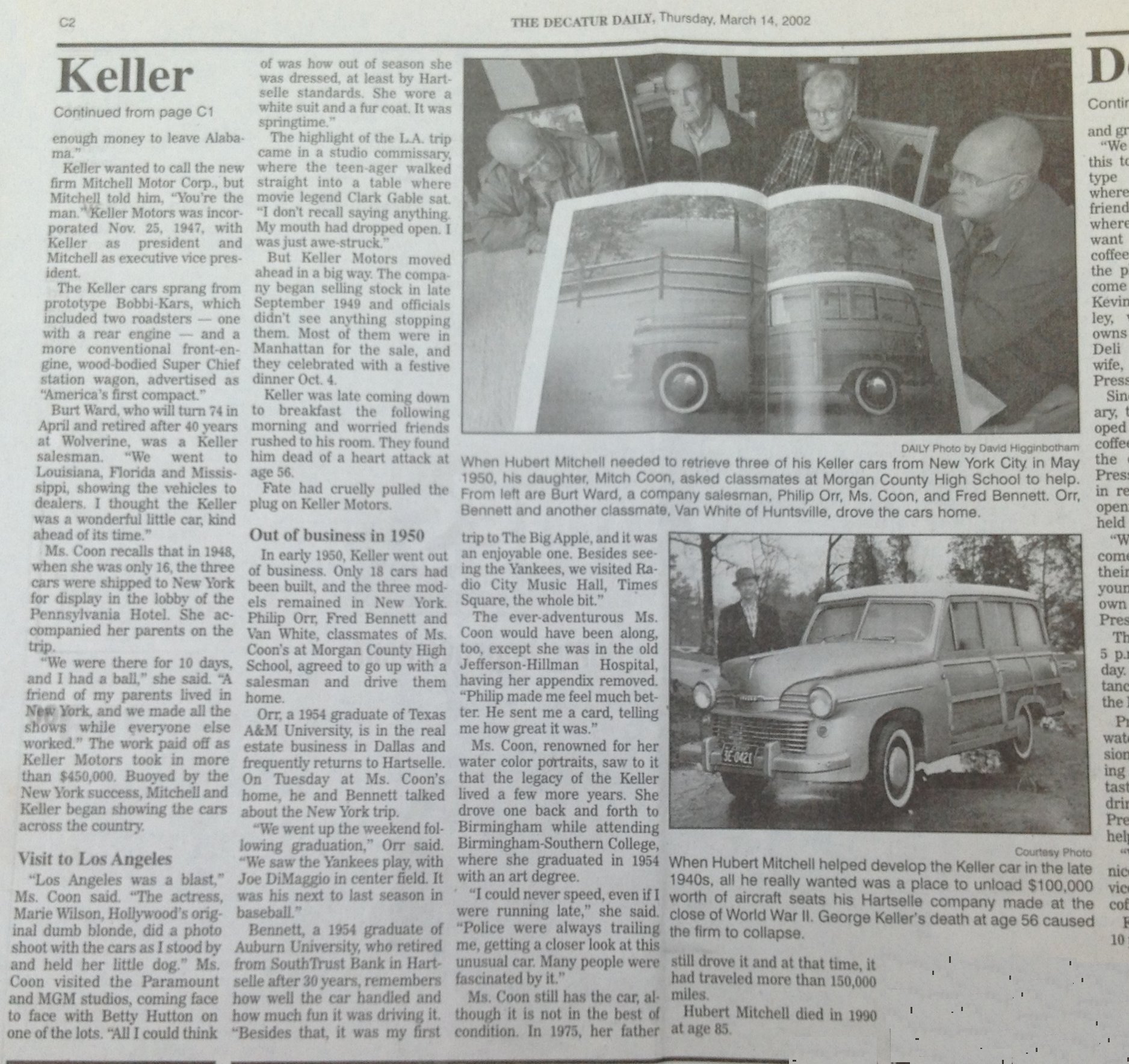

The pocketbook behind

this takeover was Hubert Mitchell, a wheeler-dealer from

Hartselle, Alabama with at least as much promotional

experience as Williams. As a boy, he built an airplane

which he successfully flew... having never before seen a

real plane, only photographs. He later ran everything

from a small-town airport to a roadside cafe, a string

of movie theaters to a theatrical agency. In the late

Thirties, he claimed to have found the outlaw Jesse

James in prison, obtained his release and booked the

90-year-old desperado into a string of Deep South grits

circuit theaters. At the time he acquired the Bobbi-Kar,

he operated the world's largest theatrical supply house

and a failing furniture factory he'd bought for the war.

It was the furniture

factory that got him interested in cars. According to

Mitchell, "I'd been making seats and upholstery for

light aircraft. During the war, the government

requisitioned all civilian planes and converted them for

military use. They threw away the original seats, and I

had contracts to build replacements in my old factory.

The manufacturers of the Globe Swiftner light aircraft,

for example, had $100,000 worth of seats on order when

the war ended. They went out of business in 1946, and I

was stuck with the seats. I was looking around for

something else to do with them."

Mitchell had ninety

employees and a 40,000 square foot factory. Acting on a

tip from the Chamber of Commerce, he went down to the

Betchtel-McCone plant that Bobbi-Kar had taken over and

spoke to George Keller. At that point, Keller, with

almost no funds, some 40 employees and an absurdly large

735,000 square foot aircraft factory, was trying to hold

things together long enough to attract investors.

"At first," says

Mitchell, "I was only interested in their car as a place

to sell my surplus seats, but George showed me how

easily I could buy the whole thing. These people were

desperate. They didn't even have the money to leave

Alabama. I had to personally loan Keller money to live

on. These people were innocent victims. They were car

people, and they were interested in staying in the

industry they'd been raised in. When Bobbi-Kar declared

bankruptcy, I decided to help.

"Keller wanted to

call it the Mitchell Motor Corporation. 'Hell,' I said,

You're the man. We'll use your name.' Dixie Motor Car

was only an interim thing, and we quickly sold out to

the new Keller Motors Corporation. The Bobbi-Kar had had

some bad publicity with potential stockholders, so we

thought we'd better change the name."

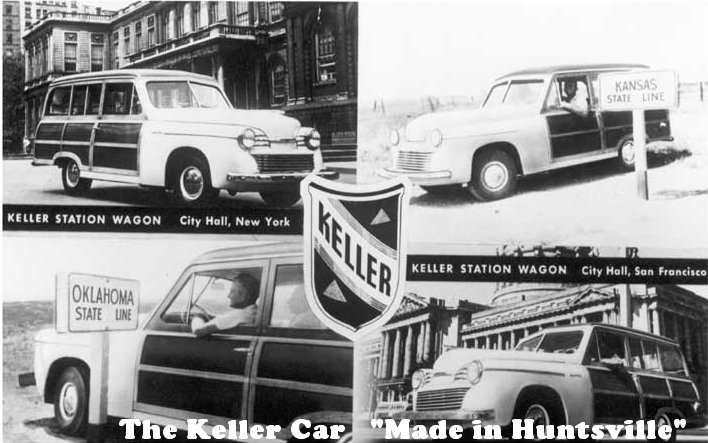

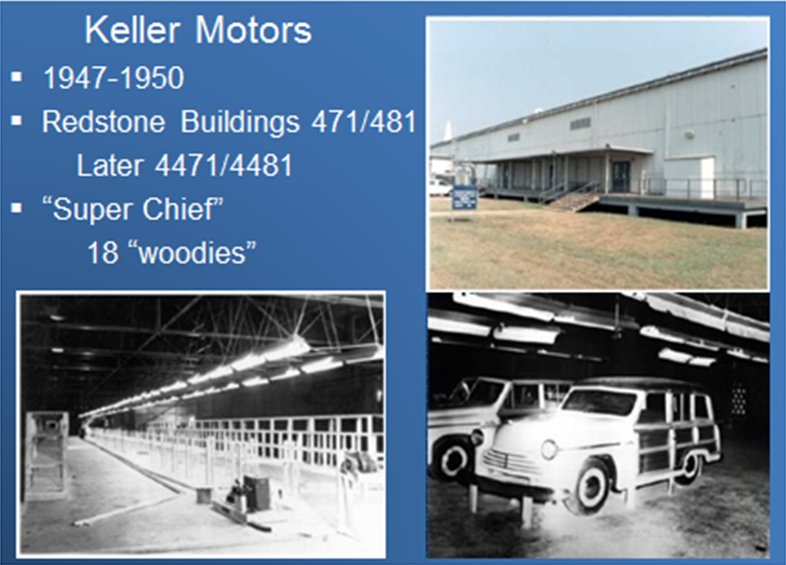

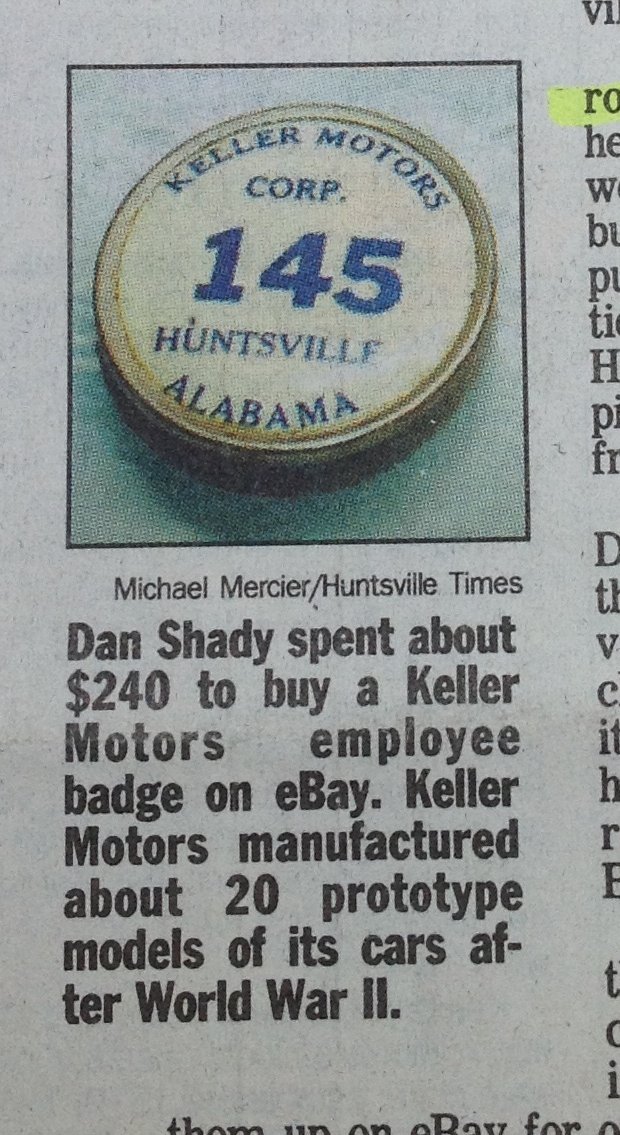

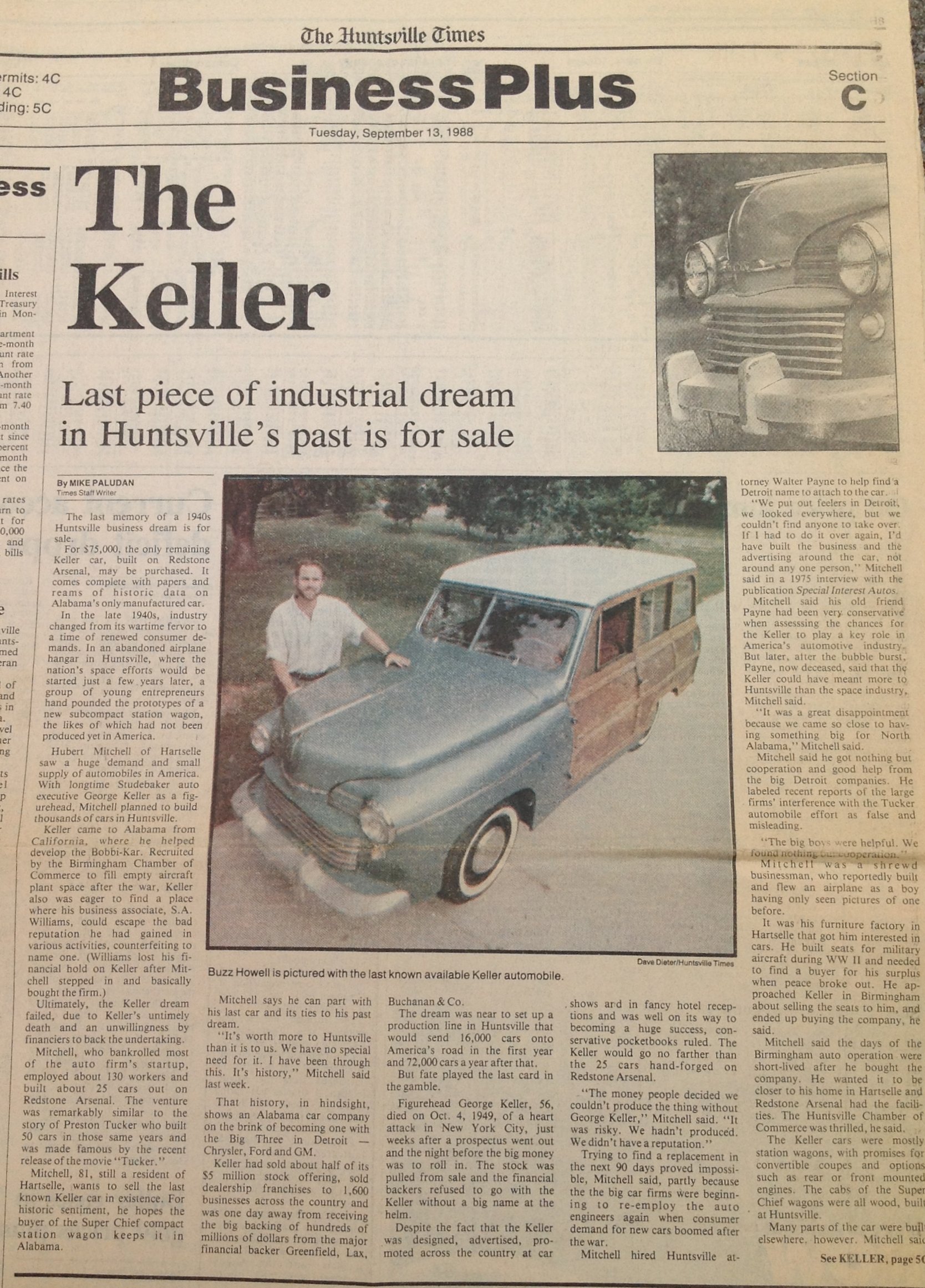

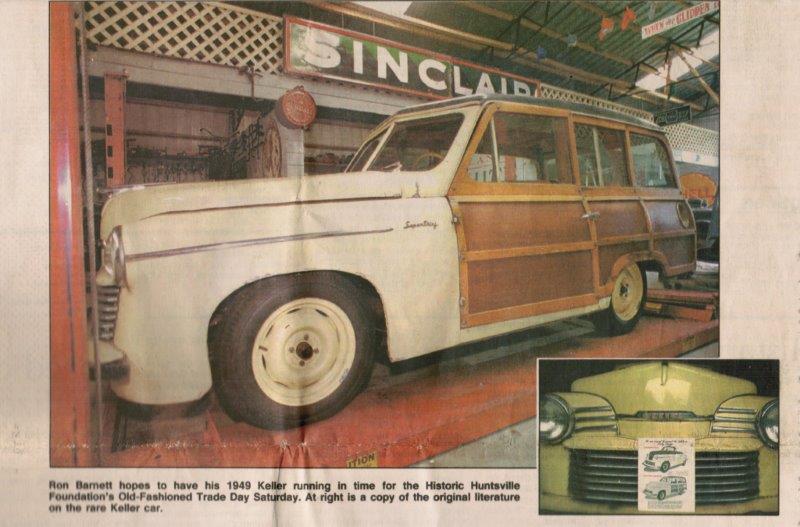

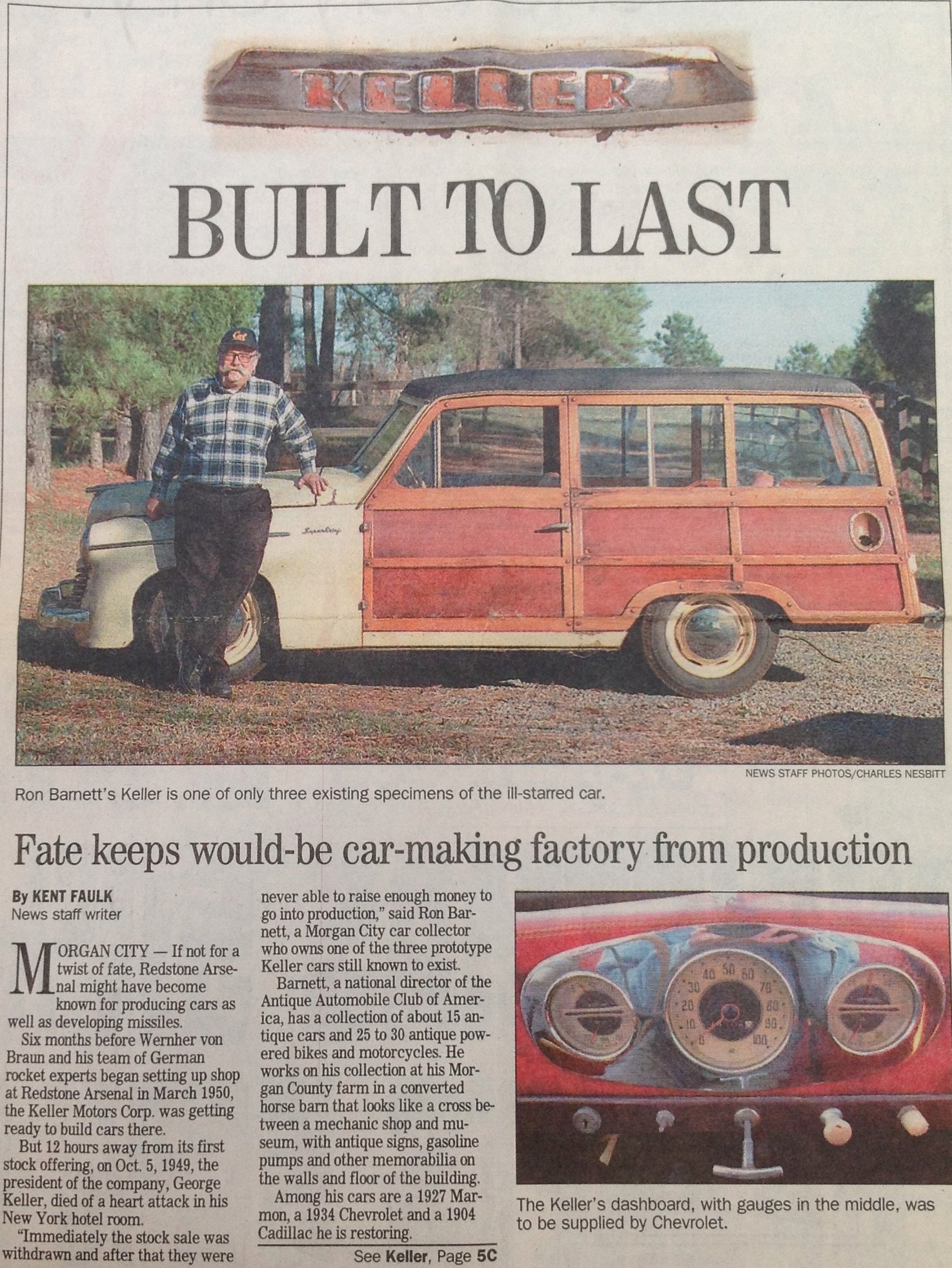

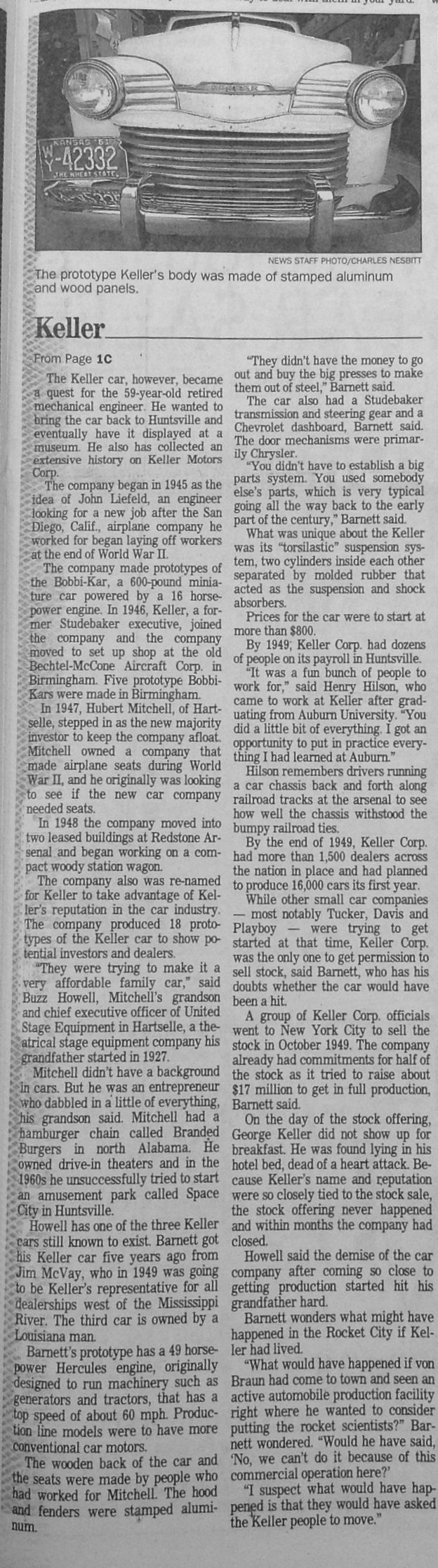

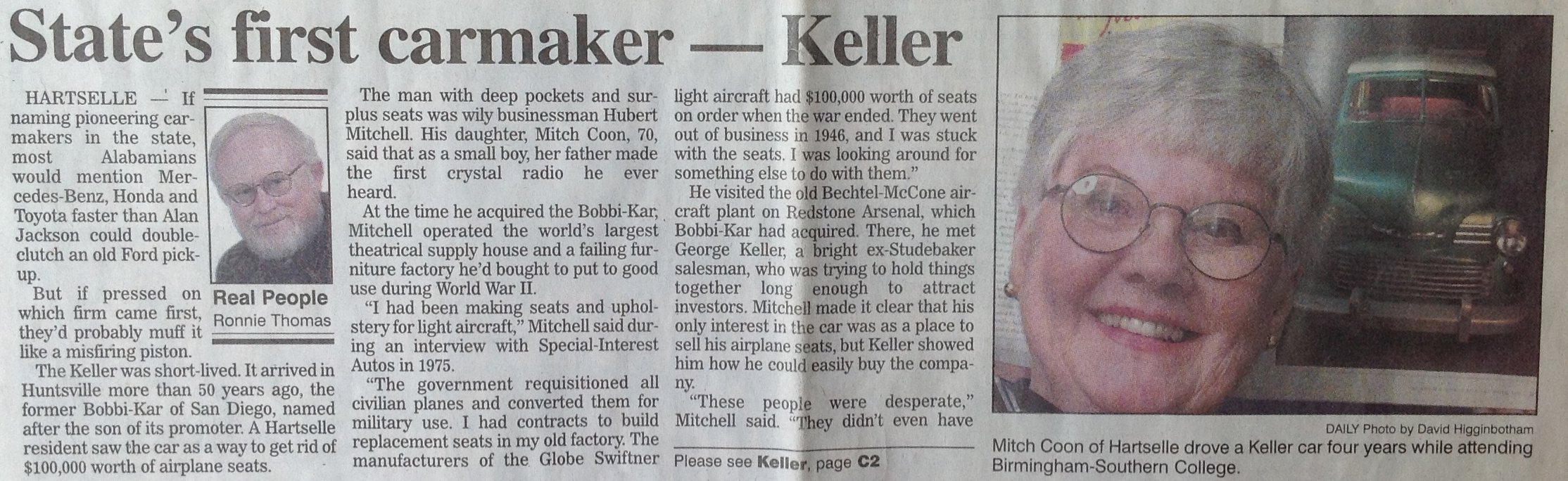

Keller Motors was

incorporated in Delaware on November 25, 1947. Keller

was the president, Mitchell executive vice-president.

They controlled a majority of the stock. Keller Motors

acquired (for $90,000) the assets of Dixie Motor Car,

which included the 25 hp prototype Bobbi-Kar that

Liefeld had constructed long ago in San Diego, a second

roadster and a more conventional front-engine woodie

station wagon, powered by a 49 hp Continental

powerplant. There were also two chassis, one

front-engine, one rear. Mitchell determined to get the

company rolling as quickly as possible, for as he says,

"During that time I was subsidizing the whole crew,

Keller included. I loaned them money until we started

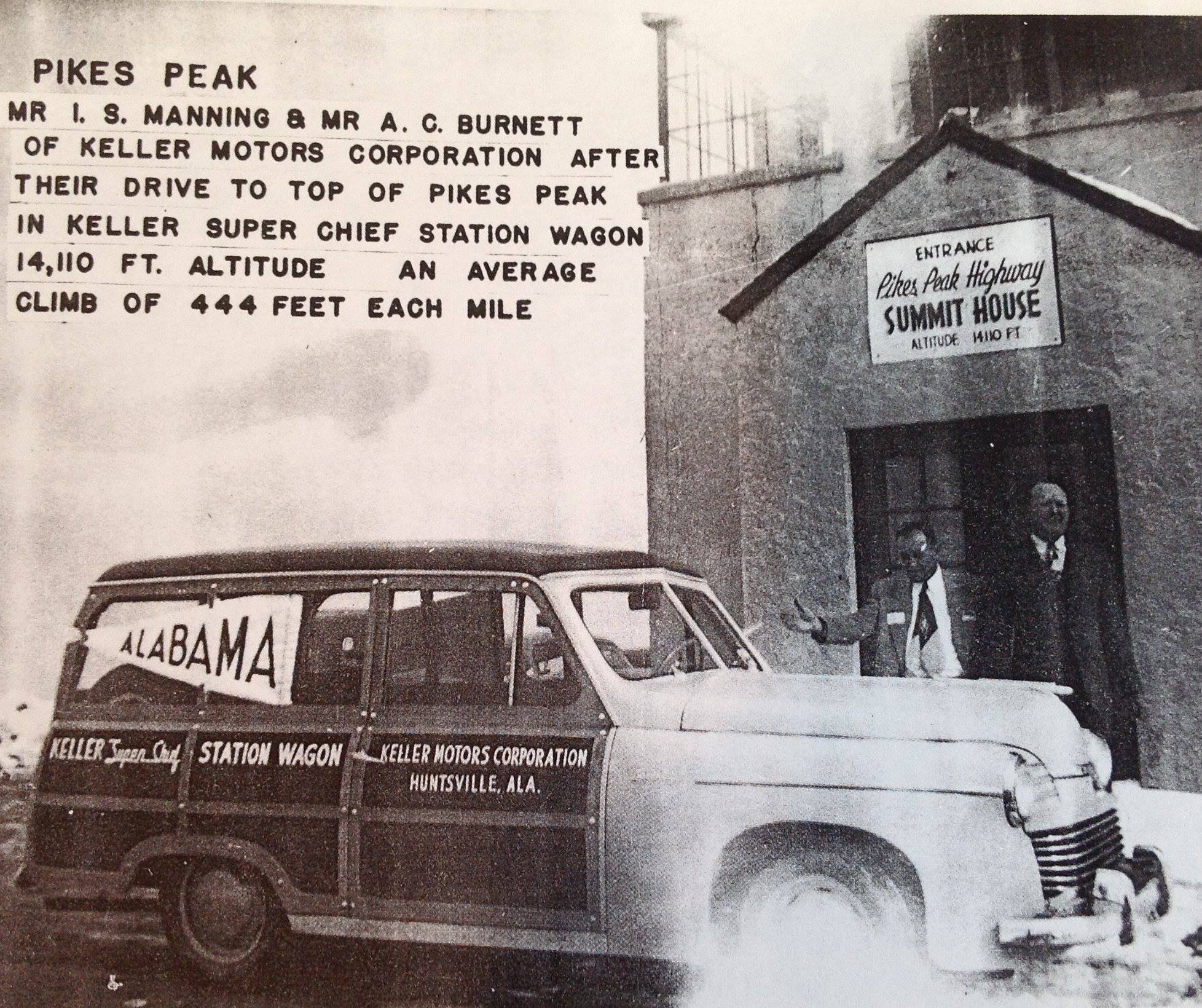

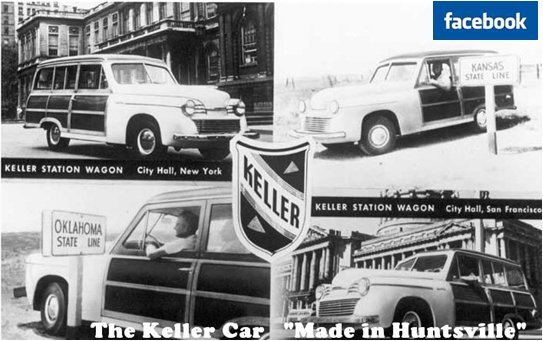

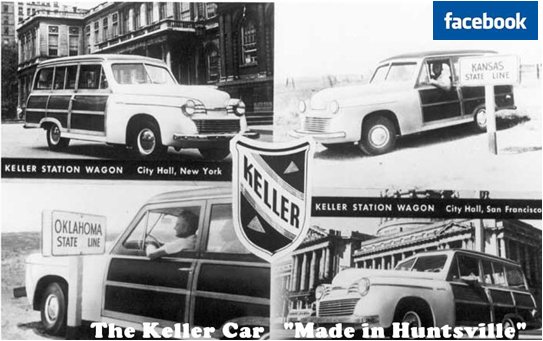

selling stock." Early in 1948, Mitchell and Keller took

the station wagon, a roadster and the rear-engine to New

York. They rented the lobby of the Pennsylvania Hotel,

and distributed a barrage of press releases and

brochures prepared by an advertising agency run by

friends of Keller's in New York. Said Buchanan &

Company, "The Keller is America's most needed car in

size, performance and price." The copy then dwelled on

George Keller's 28 successful years in the automobile

industry, making him out to be Walter Chrysler, Charlie

Nash and the Dodge Brothers all in one. The flamboyant

copy was all in the service of drumming up interest in

the "new" car, and resultant sale of dealer franchises.

In many ways, it was Bobbi-Kar of California all over

again.

The times were still

ripe for that sort of scheme. Detroit wasn't taking any

new dealerships in 1948, since the factories couldn't

keep their current dealers supplied. But not only were

there legions of people ready to pay inflated postwar

prices for new cars, there were hundreds too, with money

saved throughout the war, ready to enter the automobile

business. To these people, even the unassuming little

Keller looked like the ticket of admission to the Big

Time.

The ticket wasn't

even very expensive. Mitchell and his Alabama sales

force took franchise orders on a city by city basis. In

fact, deposits were often taken from a number of people

for the same territory. "That way," says Mitchell, "we

could choose the best potential dealer. Of course, we

returned the deposits to the rest." According to

Mitchell, "We didn't know how well we could sell

franchises, but cars were hard to come by and the people

appeared willing to pay."

Keller Motors took in

over $450,000 on their first ten-day trip to New York.

As Mitchell recalls, "We wanted seven dollars per car.

For an area that we figured would accept a thousand cars

a year, we'd ask for $35,000 for a five year contract."

Franchise fees, at first, were a fraction of that

amount. Andy Pappas of Shreveport, Louisiana, for

example, says he paid only $20,000 for the right to sell

Kellers in twenty Louisiana parishes. He, in turn sold

the rights to some of these counties to other

individuals for $1000 per parish. But this was early in

the Keller story. As the franchise scheme succeeded, the

potential of each territory was deemed greater, and the

price rose accordingly.

Following the

astounding New York success, Mitchell and Keller began

showing the cars all around the country. The roadster,

station wagon and chassis were shown in hotel lobbies,

civic centers, trade fairs-anywhere an audience might

form. From Baltimore to Davenport, Milwaukee to Los

Angeles, Mitchell and Keller barnstormed the country

with their prototypes throughout 1948. Although the

publicity releases promised production cars "in four or

five months" at a retail price of $848, Keller Motors

was a long way away from actually making cars.

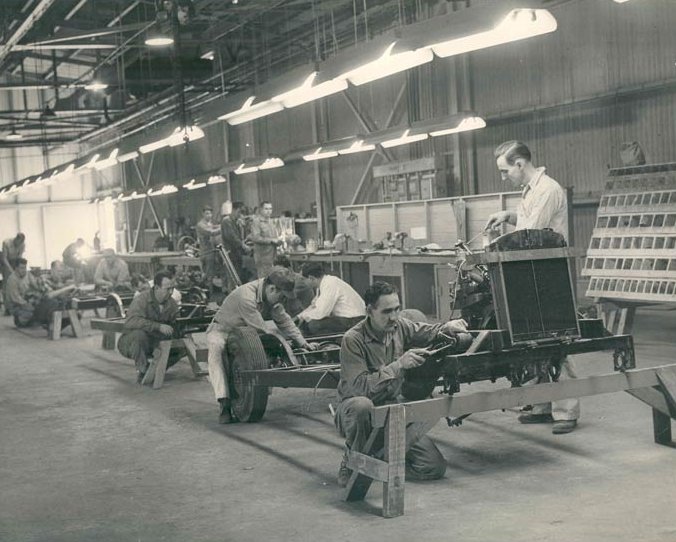

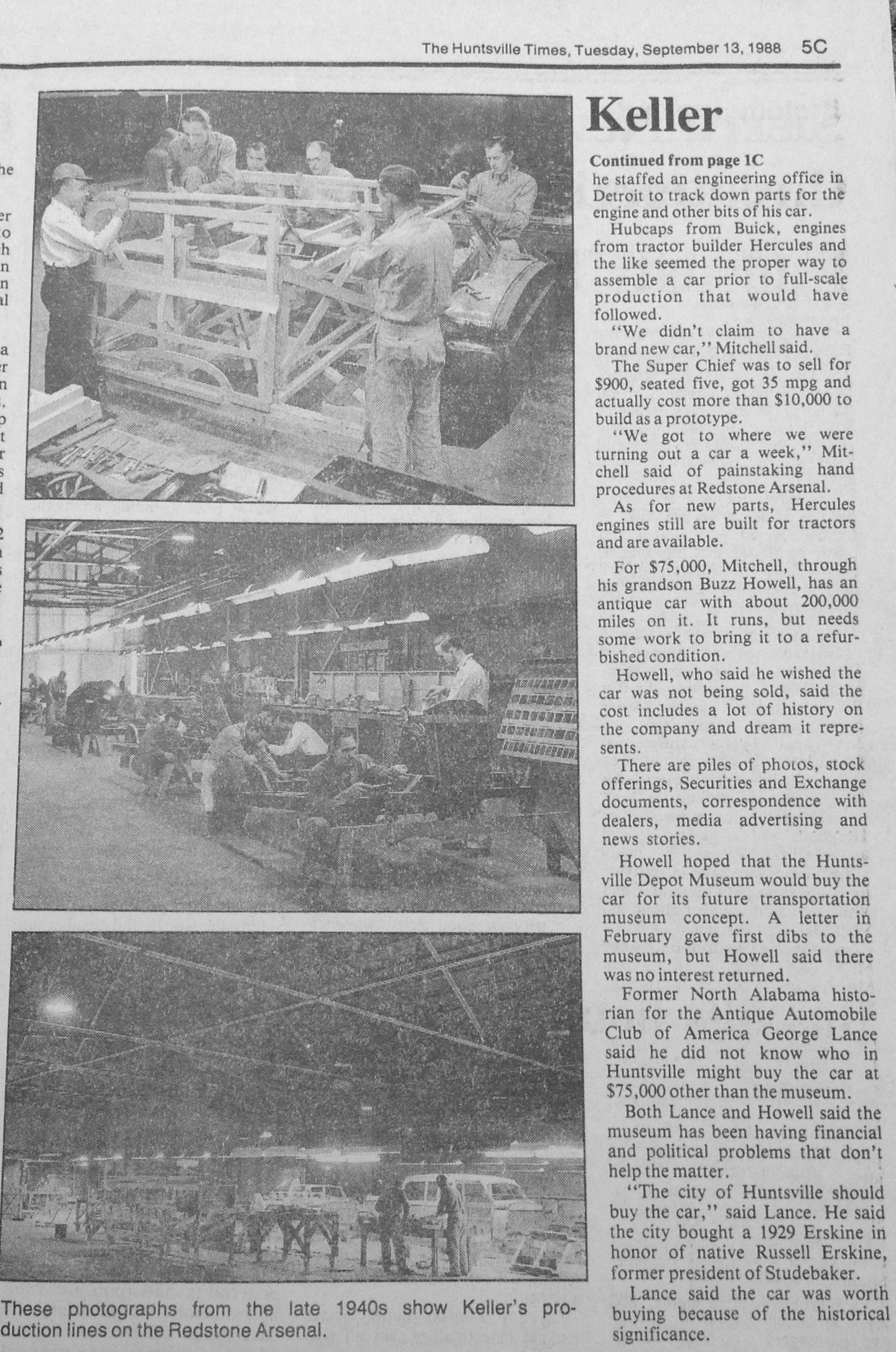

A great deal of the

franchise money was spent on development of Liefeld's

original design. Along with the huge plant in the

Huntsville Arsenal that Williams had first leased and

Keller now staffed with a skeleton crew, another office

was opened in Detroit, close to the center of the auto

industry. Keller was unsure about Liefeld's design, and

demanded that friends of his--qualified engineers from

Chrysler, Packard and Studebaker-should look over every

aspect of the prototypes. In addition, since the

Bobbi-Kar--and hence the Keller--had been deliberately

designed to use as many proprietary parts as possible,

it made good sense to have a Detroit office in direct

contact with the suppliers, most of whom were clustered

around the Big Three.

Liefeld soon had a

staff of nearly 70 designers, engineers and purchasing

agents on the payroll. According to him, in the

aftermath of the unfavorable publicity that swirled

around the Tucker, Davis and Playboy stock schemes, the

SEC kept a close watch on Keller Motors. In order to

prove that the company did in fact intend to make cars,

Liefeld was required to obtain quadruplicate copies of

all design drawings, purchase orders and letters of

commitment from suppliers, noting exactly what parts,

how many and when they would supply these items to

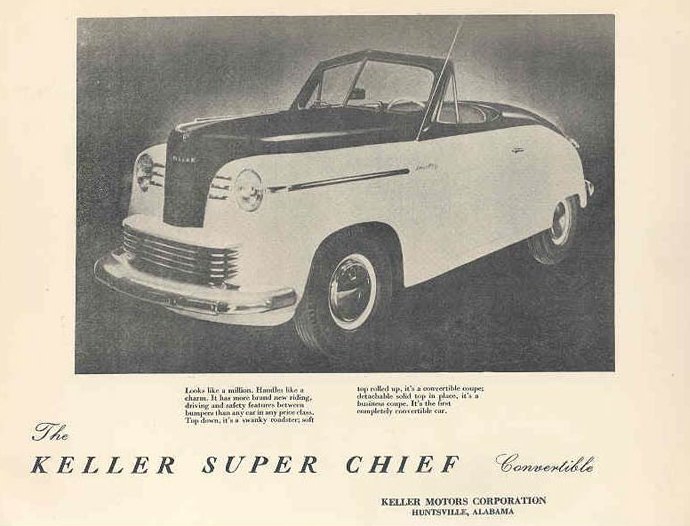

Keller. The actual design of the car was changed very

little over the years except that the rear-engine

roadster was dropped in favor of a conventional

convertible to go along with the station wagon as to

better use proprietary parts.

According to Liefeld,

they received a lot of help from major industry figures,

mostly through Keller's contacts. But the Detroit firms,

he says, "were definitely not interested in getting into

the small car business. They told us in effect, 'there

is a market for a small car, but it is a limited market,

and we don't want to touch it unless we're absolutely

forced to. We think a small company like yours is the

right company to do this and we'll do all we can to

help.'"

Keller's contacts

soon gave their approval to Liefeld's straightforward

design. The car, it seems, was deemed acceptable. The

franchise dealer network, too, was rapidly becoming a

reality. The real problem--and the principal cause of

delay--was the need for some $5-million to pay for

production tooling and initial supply of parts. A common

stock sale was the only solution. The father of Keller's

account executive at Buchanan & Company was the head of

Allen and Co., a major stockbroker. He agreed to handle

the stock sale, but in turn, subcontracted with

Greenfield, Lax & Co.--an affiliate of Lehman

Brothers--to sell the $5-million worth of stock.

"For a period of two

and a half years," says Liefeld, "we were on the

defensive with the SEC. Playboy, Tucker and Davis all

had indictments against them. Keller was the only

company that--throughout the period--stayed clean. After

$130,000 in attorney's fees, the SEC said in effect,

'we're awfully sorry, fellows, you're clean as a

whistle."

When the final

approval was granted, Greenfield, Lax wasted no time in

issuing an extremely detailed prospectus. Dated

September, 1949, this document indicates that Keller

Motors had spent some $1.25-million, divided equally

between promotional expenses, design and development and

the establishment of some 1,523 dealer outlets (the

final number of dealers signed up was 1,689). In

typically-guarded stock prospectus language, the firm

indicated that while it had made substantial progress in

development, it did not "represent or infer that it has

solved the principal problems of the business in which

it intends to engage." Recognizing "the development and

improvement of an automobile is a process of almost

continual change," the corporation modestly admitted

that "the final model of the completely designed

American automobile has not yet been manufactured, and

we do not undertake to do so."

A further disclaimer

warned the unwary that "the Keller Motors Corporation

does not represent or infer that it will attain

commercial production of automobiles (but will put forth

its best efforts to do so) or realize collection on said

notes as the future is unknown." Throughout the

prospectus--as on every dealer franchise agreement and

application form--it was stated very clearly that no

money would be refunded should the corporation's efforts

fail and no cars be sold. This scarcely seems to have

deterred investors.

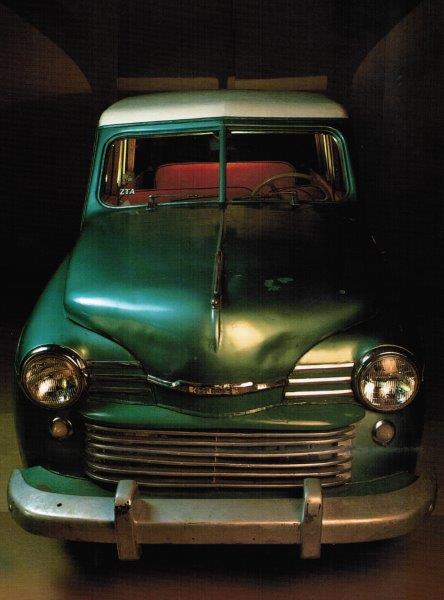

In the prospectus,

Keller's rationale for concentrating on a compact woodie

station wagon was elaborated in detail. They argued that

the population shift towards the suburbs would guarantee

an expanding market for station wagons, a true enough

assumption as it turned out. The prospectus pointed out

that 110,000 station wagons had been sold in the U.S. in

1948. Keller scheduled production for 16,000 its first

year. If this first hurdle could be overcome, they

intended to produce 72,000 cars per year... capturing a

whopping three-quarters of the existing market.

More realistically,

the prospectus did explain that prices of competitors'

station wagons were often higher than the sedans upon

which they were based. Since Keller planned to

concentrate primarily on the construction of station

wagons--and small ones at that--their price could be

substantially lower. Low enough, they hoped, to attract

buyers away from more expensive marquees. Keller did

admit, however, that such a plan was ambitious, and

since low-price competitors (notably Plymouth and Dodge)

had already introduced all-steel wagons, this might

constitute real competition which "could adversely

affect the company's position."

Actually, building

the Keller bodies of wood solved a number of problems.

Wood bodies meant that expensive tools and dies would

not be needed. Cheap Alabama labor could screw and glue

together all the bodies that Keller might use. In

addition, of course, Hubert Mitchell already had his

rather inadequate wood working plant that he was only

too ready to unload on the corporation. At the same time

he was supporting the members of the company with

personal loans, he sold his furniture factory to the

corporation for nearly three times its assessed

valuation, a fact brought out only later.

Of course, by late

1949, when the stock prospectus was issued, the

wood-bodied station wagon was already an anachronism.

Wood bodies needed careful upkeep, they were slow to

produce-requiring much hand labor-and they were prone to

rot, squeak and sag. For Keller, the woodie was an

acceptable short term answer in order to quickly get

into production, but disastrously limited in the long

run.

And seemingly, Keller

had no ideas for subsequent models. No plans, prototypes

or even sketches were made for the cars that would

necessarily have had to follow the station wagon in

succeeding years. If anything, the Keller line was

shrinking. George Keller himself never believed in the

roadster-with engine in front or rear-and although the

sales team continued to show it in hotel lobbies across

the nation, it had privately been dropped from

production plans.

On June 30, 1949,

Liefeld closed the Detroit design office and moved back

to Huntsville. Although he stated that all was in

readiness to begin production, at the time of the stock

sale no contracts formally existed with suppliers of

parts, raw materials or labor unions. He did indicate

that he thought pans and labor would be no problem. At

this same time, George Keller finally realized that the

Mitchell furniture factory was much too small for body

production. Instead, it would become the final depot

where completed cars were crated for shipment.

As the summer of 1949

rolled on, Keller Motors prepared for the autumn stock

issue that would decide its fate. Dealers continued to

sign up. Of the 1,523 franchises put out, 117 were

already handling competitive makes, 150 were used car

dealers, 91 were service station owners, 391 owned

garages and the remaining 846 "have had experience in

the sale of new and used cars and in such related

businesses as tractors and farm implements, auto parts

and accessories." The dealer mix resembled that of

Davis, Tucker and Playboy. . . predominantly little folk

who saw in Keller a cheap ride down the road to riches.

The stock sale began

in late September, 1949. And within days, Greenfield,

Lax had sold half the issue. The Keller people were

ecstatic. Finally, it seemed, after three years of

travail, they were about to reach the payoff. Most of

the officers of the company were in Manhattan for the

sale, keeping a euphoric count as each hinder came into

the broker's office. There was no stopping them now.

They celebrated with a festive dinner on the fourth of

October.

George Keller was

late coming down to breakfast on October 5, 1949.

Worried friends rushed to his sumptuous room in the

Hotel Algonquin, and found him still in bed. Dead of a

heart attack, the coroner said. He was 56-years-old.

Fate had cruelly pulled the plug on Keller Motors.

Hubert Mitchell's

idea to build the company and the advertising around

Keller rather than the car had succeeded beyond his

wildest dreams. With Keller gone, rightly or wrongly,

Allen and Co., Greenfield, Lax, Buchanan & Company, many

dealers and even most of the employees believed there

was no one left who could guide them, even though the

car design was set, the dealer network established, the

stock partly sold. Despite the pleading of Mitchell and

Liefeld, the stock was withdrawn from sale. To

Mitchell's horror, the Buchanan copywriters had believed

their own hyperbole, and convinced the others, too.

The brokers gave

Mitchell 90 days to find another Keller. Says he, "We

hired a legal firm, the best one in Huntsville. We put

out feelers in Detroit, we looked everywhere, but we

couldn't find anyone to take over. If I had it to do

over again, I'd have built the business and the

advertising around the car, not around any one person.

But at the time, it seemed like the thing to do.

"You can't imagine

how hard it is when you want to help people--you see

their excitement and eagerness--but you just can't. We

spent our three months looking around. Then we put the

company into receivership. We had to. Finally, early in

1950, we went out of business. It took a lot out of me

physically and mentally, and of course, I lost a lot of

money. We had high hopes, and came very close. But it

wasn't to be."

"What we did," says

John Liefeld, "was fold our tents. We had about $66,000

in assets left and we had about $53,000 in debts. We

paid everyone off, and that was it. What it amounted to

was that with Keller gone, we had no spark plug left in

the engine." In retrospect, it's probably fortunate that

no one stepped forward to regroup the Keller's

leaderless forces. By late 1949, when George Keller

died, his "ideal car for the poor man" was already a

fallacious concept. Time had passed him by. In 1945,

when Williams and Liefeld began, in 1946 when Keller

joined them, even as late as 1947 and '48 while they

dithered with the SEC, the homely little wagon built of

proprietary parts might have sold long and well enough

to get them started in the car business. In those years

the competition was still selling prewar designs, and

the assembly lines could not move fast enough to fill

the demand. But by 1949, real postwar competition had

appeared, and the Keller stood revealed as an ungainly

little anachronism, hopelessly outmoded.

The Keller

organization was never too strong. They had few

experienced car people. They had no future plans. They

had a weak dealer network, largely composed of amateur

speculators hoping to turn a quick buck in the

car-hungry postwar period. And too, the Keller staff

foolishly acted like nouveau riche heirs, riding in

corporate Cadillacs and Buicks, crisscrossing the

country to attend expensive openings, maintaining

hundreds of employees in three different locations all

to produce prototypes of a ear that had been mostly

designed before Keller Motors, per se, existed. Although

they had taken in nearly $2-million in dealer franchise

fees, Keller went under with little more than $10,000 in

the coffers. Indeed, finances were so tight that at the

end, the Hotel Buckingham in New York was forced to sell

off a station wagon prototype that had been displayed in

its lobby in order to cover Keller's outstanding bills.

If anything was wrong

with Keller Motors, it was an all-too-familiar

combination of inexperience, poor timing and over

ambition. Keller was certainly no different from many

others who ached to build their own automotive empires

in the fair spring days that followed close behind the

cold years of war. Indeed, George Keller had more hope

of accomplishing his goal than most, though he was never

in the same league with Henry Kaiser and Joe Frazer, and

they too were unsuccessful. But Keller could not lead

his inept confederates to success merely by strength of

will. And without him, it seems, they were nothing.

Perhaps indeed, the stockbrokers' assessment was right

after all. "Le Patron est mort, la voiture est morte

aussi." |

1917-1924

1917-1924

THE KELLER CAR

THE KELLER CAR portions from "Special Interest Autos" September/October 1975

and the Redstone archives

portions from "Special Interest Autos" September/October 1975

and the Redstone archives

of the 1949

"Barnett" Keller Car:

of the 1949

"Barnett" Keller Car: